A rendering of Aerofarms’ completed new facility in Newark, New Jersey. Aerofarms

Picture a vegetable farm, and you might imagine growers digging through dirt and planting rows of seeds. Besides the occasional spray of pesticide and pH check, all the plants need are sunlight, fertilizer, and water.

AeroFarms , a vertical farm in Newark, New Jersey, is nothing like that.

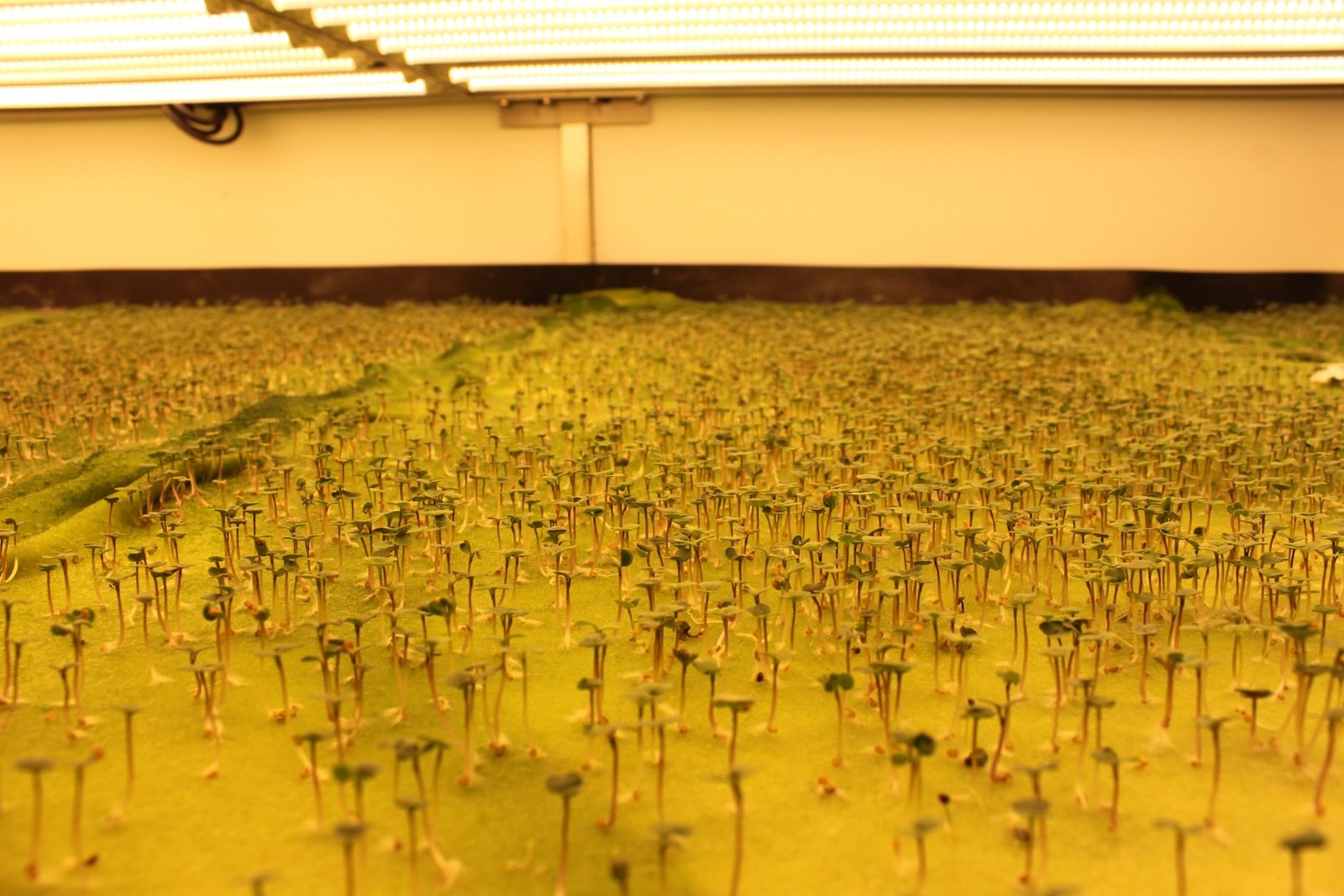

Instead of stretching down through the soil, plants are placed in trays stacked 30 feet high. The greens don’t thrive on sunlight, basking in LED lights instead. Fans spin continuously, and a sprinkle of fertilizer feeds the plants every few hours. Farmers wander around in coverall suits, rubber gloves, and hairnets.

A row of lettuce at Aerofarms. Leanna Garfield/Tech Insider

A row of lettuce at Aerofarms. Leanna Garfield/Tech Insider

Stacks of these lettuce-growing systems fill AeroFarms’ new 69,000-square-foot warehouse in Newark, which will become the world’s largest vertical farm when it officially starts production this spring. The farm will produce 2 million pounds of leafy greens a year, AeroFarms’ Chief Marketing Officer Marc Oshima tells Tech Insider.

When I visited AeroFarms in February, the walls were still going up, and two giant mounds of dirt and rocks sat out front. Nonetheless, Oshima says it will open by June.

The goal is to to optimize the growing algorithms of 250 different types of plants, including kale, arugula, and mizuna plants. Once the farmers figure out the best way to grow the greens, they can replicate the method every time. AeroFarms then plans to send out the greens to places in the local metro area that don’t normally have access to fresh produce.

“Cities have a lot of mouths to feed. We have population growth, urbanization, and we need better ways to feed humanity that are sensitive to the environment,” AeroFarms’ CEO and founder David Rosenberg tells Tech Insider. “Vertical farms are one of many solutions.”

Vertical farms are increasingly sprouting up as an antidote to urban food deserts, or areas where it’s difficult to find fresh produce. A company called FarmedHere, for example, is preparing to start construction on a 60,000-square-foot vertical farm in Louisville, Kentucky in August. Other farms take the model a step further by replacing farmers with robots, like Spread’s vertical lettuce farm opening in Japan in 2017 .

Compared to traditional farming, vertical farms can be significantly more productive using a lot less space. AeroFarms will produce roughly 6.4 million 5-ounce packages of lettuce, or 10 times the amount of a typical 1,300-acre farm in Central New York, according to a recent report by Cornell University.

Normally, the lettuce consumers buy doesn’t reach the shelves until 5 to 7 days after it’s harvested, because it’s grown on farms or greenhouses hundreds of miles outside urban areas.

Lettuce sprouts at Aerofarms. Leanna Garfield/Tech Insider

Lettuce sprouts at Aerofarms. Leanna Garfield/Tech Insider

AeroFarms, on the other hand, will grow greens just 15 miles from Manhattan and deliver batches immediately after they’re harvested. The company has already partnered with organic wholesaler Farmigo and will sell its lettuce in NYC grocery stores for a price comparable to organic lettuce.

There are environmental advantages to AeroFarms’ techniques, too. The Newark vertical farm will use 95% less water and 50% less fertilizer than traditional vegetable farms, Oshima says. Since the greens grow indoors, they aren’t exposed to pests. That means there’s no need for pesticides.

The farmers also have complete control over the plants. They tailor the LEDs to specific spectrums and intensities and adjust the ventilation, temperature of the roots, and sprays of water and nutrients to grow the richest greens possible, Oshima says. Just by adjusting the algorithm, the farmers can theoretically make the plants sweeter or boost levels of vitamin A.

AeroFarms has built nine vertical farms around Newark since 2004. While this latest farm is the largest, the company also plans to launch more farms in other east coast cities, shipping greens locally within a 30-mile radius. Although the company is only growing greens right now, Oshima says it will eventually experiment with other fruits and vegetables.

The stakes for AeroFarms are high, with investors like Goldman Sachs and Prudential Financial backing the company to the tune of $39 million .

A number of promising recent vertical farm operations have already failed. In 2015, Google’s Alphabet X tried to create an automated vertical farm , but the company later abandoned the project because it couldn’t figure out how to grow staple crops (like grains) using vertical farming techniques. VertiCrop, North America’s first vertical farm, was founded in 2011 and declared bankruptcy after only three years. When it comes to providing nutritious crops to the world, greens only take you so far.

Leanna Garfield/Tech Insider

Leanna Garfield/Tech Insider

Critics of vertical farming worry about how much energy the technique wastes, since LEDs need to shine 24-7 to produce a high volume of plants. According to some research, vertical farms like AeroFarms can generate 10 times the carbon footprint of traditional vegetable farms, according to Louis Albright , the director of Cornell University’s Controlled Environment Agriculture program.

“What troubles me the most is that it [vertical farms] started out as a solution to food miles and then carbon footprint,” he tells Tech Insider. “But it increases the carbon footprint by an order of magnitude.”

Since energy costs are so high, it’s uncertain whether vertical farmers can grow greens at an affordable price long-term. AeroFarms uses a proprietary energy-efficient lighting system, Oshima says. He wouldn’t reveal exactly how it works or saves energy.

Still, some vertical farms initiatives have found success, both in the US and abroad. MIT’s Media Lab recently launched an open source farm, called City Farm , with hopes that its growing algorithms will be used by vertical farmers elsewhere. Japan’s Mirai (which translates to “future”) operates in 12 locations around the country, including a 25,000-square-foot farm that can harvest 10,000 lettuce heads a day.

And as energy technology develops, LEDs will only become more energy-efficient. Between 2012 and 2014, LED lighting efficiency jumped about 50%, according to a report by the US Energy Information Administration. By 2020, it may climb another 50% as costs drop.  As a demonstration, a row of greens sit under red light, the spectrum (normally undetectable by the human eye) that the plant “sees.”Leanna Garfield/Tech Insider

As a demonstration, a row of greens sit under red light, the spectrum (normally undetectable by the human eye) that the plant “sees.”Leanna Garfield/Tech Insider

At AeroFarms, a new employee is responsible every week for sharing a new recipe that uses the greens grown onsite. The day I visited AeroFarms, it was a simple salad with watercress, red romaine, and mizuna lettuce. The lettuce was an explosion of spicy and sweet. I was so surprised by how intense the leaves tasted.

Is this what we’ve all have been missing on our plates? If AeroFarms proves its farm is truly environmentally sustainable (which may take a third party to decide) and offers a viable business model, it could be the unlikely key to unlocking big harvests of tastier, fresher greens.

Source: Inside the world’s largest vertical farm, where plants stack 30 feet high

Other places to find me: